You don't have to be a sports fan to appreciate the upcoming Super Bowl; if you're a tech geek, then Mercedes Benz Stadium in Atlanta, home of Super Bowl LIII, provides enough digital technology to take your breath away. We take a look at the network infrastructure in NFL's newest stadium, and how it showcases what has become an important aspect of the game day experience for sports fans: network connectivity. You might be surprised at some of the figures...

The Networked Sports Event

Over the past decade or so, fans' expectations for in-stadium connectivity at sporting events have increased drastically. Because who would want to go to a game and actually watch it, right? Selfies, live Facebook videos, Instagram stories...much of a stadium's technology is geared towards keeping people connected to their social media profiles so that they can share, share, share.

A big part of this connectivity is Wi-Fi. Network analytics show that in 2018, the average number of in-stadium Wi-Fi users at regular season NFL games was just over 30.000...per game. Considering that the average NFL stadium has a seating capacity of 70.000, almost half of the fans attending a game connect to the Wi-Fi. This obviously results in a lot of data transferred, and in 2018 the average was 3.8 terabytes per game, double what it was in 2014.

All of this means that modern stadium design has to be geared towards keeping users connected, and Mercedes Benz Stadium, home of Super Bowl LIII, is just about the pinnacle when it comes to this.

The Connected Stadium

Finished in 2017, it cost around 1.6 billion dollars, and it certainly is a jaw-dropper. For an amount roughly the equivalent to the nominal GDP of San Marino (give or take a few hundred million), you get a nifty retractable roof with petals that can be moved about at the press of a mouse button, and a 360-degree, 63.000-square-foot HD Halo Board.

Finished in 2017, it cost around 1.6 billion dollars, and it certainly is a jaw-dropper. For an amount roughly the equivalent to the nominal GDP of San Marino (give or take a few hundred million), you get a nifty retractable roof with petals that can be moved about at the press of a mouse button, and a 360-degree, 63.000-square-foot HD Halo Board.

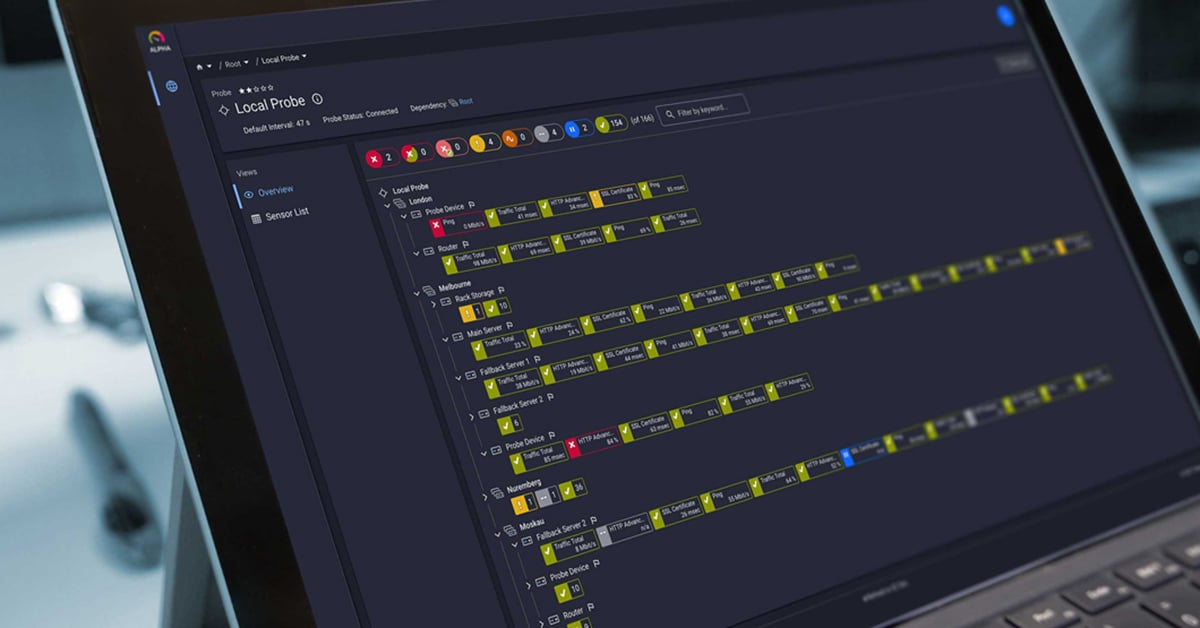

But once you get past the flashy roof and the almost redundantly large video screen, the network infrastructure running out of view beneath the surface is just as impressive. The stadium's very bones were crafted to deliver a flawless connected experience. The long and short of it: 71.000 people could comfortably stream from their seats at the same time.

Here's how the infrastructure was designed to cope with this:

Fiber-Optic Network

.jpg?width=300&name=Atlanta_August_2016_33_(Mercedes-Benz_Stadium).jpg) 4.000 miles of fiber-optic cables transfer data to and from access points. When you consider that Levi's Stadium in San Francisco, which was completed in 2014 and is itself considered a technological marvel, has "only" 400 miles of fiber-optic cables, the scale of what we're talking about here becomes clear.

4.000 miles of fiber-optic cables transfer data to and from access points. When you consider that Levi's Stadium in San Francisco, which was completed in 2014 and is itself considered a technological marvel, has "only" 400 miles of fiber-optic cables, the scale of what we're talking about here becomes clear.

So what's connected? All kinds of things. LED displays, the audio system (4.200 speakers and 1.000 amplifiers), IPTVs (2.500 of them), security access control systems, security cameras, and Point of Sale systems are just some examples. To handle the diverse devices and technologies connecting to a single network, IBM (who provided the network design and implementation) devised what they call a "Unified Stadium Technology Platform".

The fiber-optic infrastructure facilitates the use of a Passive Optical Network, or PON. A PON delivers fast and reliable Wi-Fi, but needs decidedly less power than an Active Optical Network. This is because powered equipment is only needed at the source and receiving ends of the signal.

There are over 1.800 wireless access points in Mercedes Benz Stadium (500 more than the next NFL stadium). Meanwhile, for wired connections, there are 15.600 ethernet ports throughout the complex.

Data Center

The stadium has its network operations and data center on-site, along with over 4 petabytes of storage capacity. About 50+ terabytes of stadium systems data is backed up to the IBM Cloud each month.

Mobile Coverage

For mobile customers not wanting to connect to the Wi-Fi, a Distributed Antenna System (DAS) provides 1.440 radio antennas and 1.590 DAS remote units to bring mobile coverage to every corner of the stadium.

Super Bowl Numbers

While normal game day streaming and connectivity numbers are pretty staggering, the Super Bowl is no normal game day. Everything is bigger and faster and more impressive, and the network requirements are no exception.  People have paid a LOT of money to be there in the flesh, so naturally there's a lot more sharing of Instagram stories and Facebook live video streams to prove it. Add in the use of the official Super Bowl app, which gives users an integrated stadium experience, and you have a lot of data that will be going through those fiber-optic cables at the same time...

People have paid a LOT of money to be there in the flesh, so naturally there's a lot more sharing of Instagram stories and Facebook live video streams to prove it. Add in the use of the official Super Bowl app, which gives users an integrated stadium experience, and you have a lot of data that will be going through those fiber-optic cables at the same time...

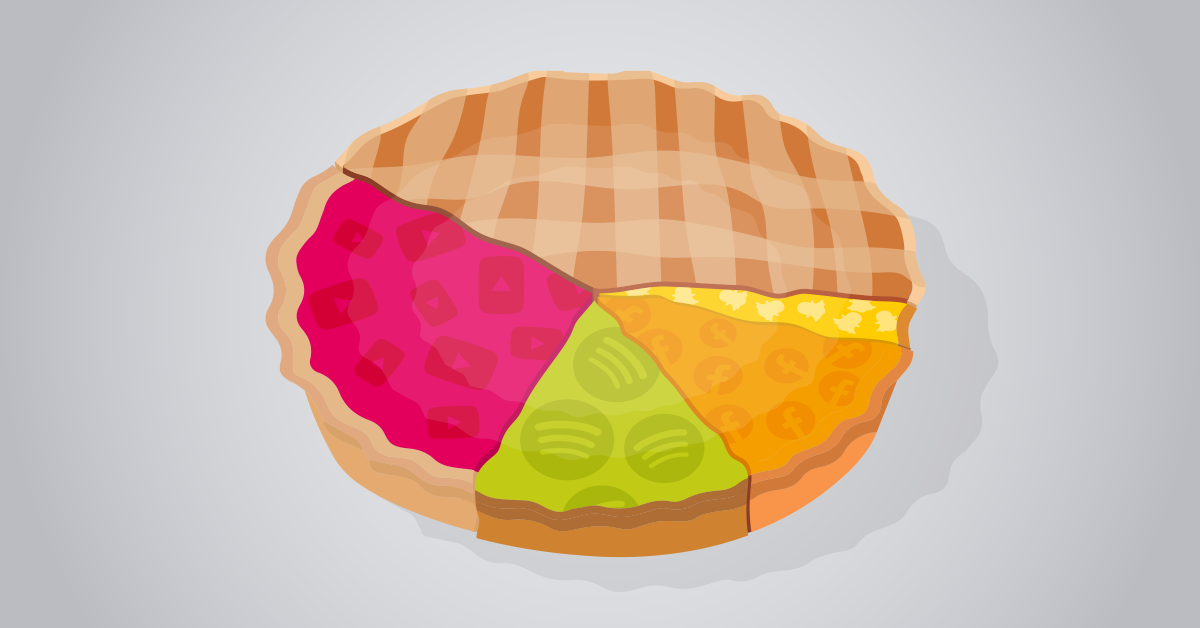

So what kind of numbers should the stadium's network operators be expecting? You can get some idea by looking at the in-stadium Wi-Fi data transfer figures from the last few Super Bowls:

- 2015: 6.2 terabytes

- 2016: 10.1 terabytes

- 2017: 11.8 terabytes

- 2018: 16.3 terabytes

The data usage over Wi-Fi has skyrocketed. Keep in mind, too, that those figures include the pre-game activities, plus the half time show. Oh, and there's also a game in there somewhere, too.

But what are the fans doing to generate so much data transfer, you might ask (or at least, I did)? At last year's event, of the 16.3 terabytes transferred, 2.6 terabytes was social networking data. 7.8 terabytes of cloud storage data—for example, photos to Apple iCloud or Google Drive—was transferred. And most surprisingly—at least for me—was 1.2 terabytes transferred for iTunes. Who is paying all that money to go to the Big Game, and then listening to their iPod? GIVE ME YOUR TICKET, DAMMIT!

And one last figure from Super Bowl LII: just over 40.000 fans connected to the WI-FI at some point during the event. That's 59% of the audience. And at the peak, there were 25.670 users connected concurrently. Considering that my phone was pretty much a glorified camera when I went to a soccer game with 60.000 people just a few years ago, connectivity for the masses has vastly improved in a very short time.

This Year's Numbers

I think it's clear that this year's data transfer figures will break another record, but it will be interesting to see if the figures start to level off. The difference between the 2017 and 2018 events was about 5 terabytes. Will usage increase by so much this year again? I guess not, but who knows? What is clear is that newer stadiums will need to be built with the infrastructure to handle a lot of data, and older stadiums will probably need to upgrade in order to keep up with fan's expectations.

Would you like to be an administrator in a stadium like Mercedes Benz stadium? Do you think this kind of infrastructure is "future flexible"? What kind of data transfers will we see at this year's event? Let us know in the comments below!

Published by

Published by

.jpg)